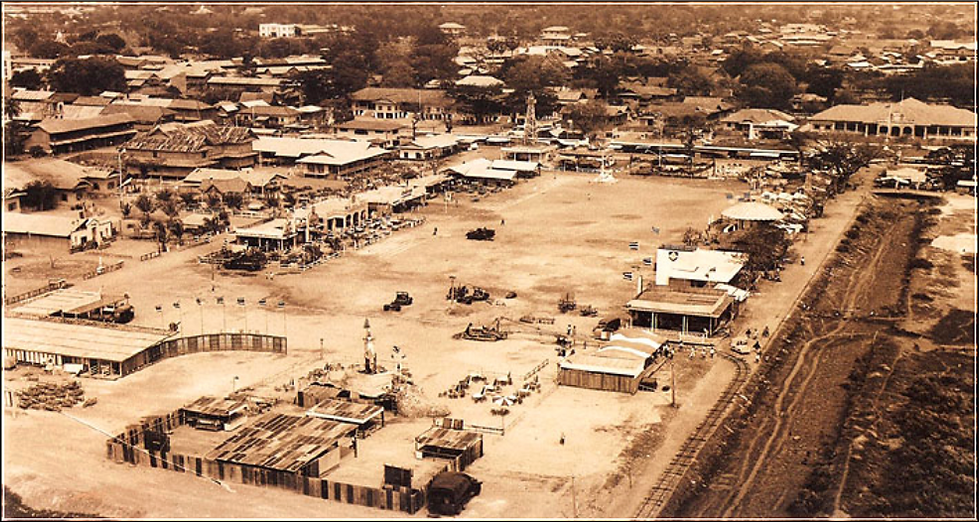

China - 1960's

- The Legacy Project

- Aug 9, 2025

- 2 min read

My grandfather’s harshest years began in 1959, during the start of China’s worst famine, known in textbooks as the Great Leap Forward under Mao Zedong. He was only six or seven, enduring constant hunger and the daily need to scavenge for food to survive.

The famine stemmed from national policies that halted farming to produce steel and iron. But villagers didn’t know how to forge metal. The products were worthless, and with farming halted, the commune lost its food supply.

In my grandfather’s commune, the famine lasted three years. Food was so scarce that everyone had to forage—wildflowers, tree bark, wild grass, and plant roots. These ran out quickly among 100 people. If you didn’t find anything, you went hungry—unless relatives shared what little they had.

When my great-grandmother got sick, she was given rice husks—a luxury saved for the ill.

Despite the famine, life continued. Children like my grandfather went to school after morning foraging. Classes ran from 8:00–11:30 a.m. and resumed from 1:00–4:00 p.m. After school, children often returned to gathering. Pencils and notebooks were sold for a few cents, but food was rarely available, making money almost useless.

Each person earned 20–30 cents a day, but with no food to buy, money had little value. Farming was discouraged and punished, labeled "capitalist" under Communist orders.

Clothing was scarce. Two people shared three pairs of pants; men and boys had no shirts—just scratchy linen cloths. These were worn for years, patched repeatedly. No one had shoes. Walking barefoot over twigs and thorns was painful—until thick skin developed.

Water came from shared wells.

In 1962, the commune was allowed to farm again. In 1977, when Deng Xiaoping came to power, people like my grandfather could work freely and finally eat enough. By the 1980s, life improved: more food, better clothing, and growing stability.

Comments